ICU Heel Protection: Starting Prevention Early

Intensive care patients face the highest pressure ulcer prevalence of any hospital setting—14.32% according to international prevalence surveys. The heels account for a substantial proportion of these injuries. And unlike many ICU complications, heel pressure ulcers are largely preventable with appropriate intervention.

Yet in the complex, high-acuity environment of intensive care, heel protection can be overlooked. The focus—rightly—is on keeping the patient alive. Organ support, haemodynamic stability, ventilation, sedation. Heel protection rarely tops the priority list. But if a heel pressure ulcer occurs then this complicates continuity of care.

This article makes the case for implementing prophylactic heel offloading as a standard component of ICU care, and examines what effective implementation looks like in practice.

ICU patients have multiple compounding risk factors.

The high prevalence of pressure injuries in intensive care isn't accidental. ICU patients face a convergence of risk factors that rarely occur together in other settings:

Complete immobility. Sedated, ventilated, or paralysed patients cannot reposition themselves. They may not move for hours or days at a time.

Reduced perfusion. Haemodynamic instability, vasopressor use, and shock states all compromise peripheral circulation. The blood supply to the heels—already limited by their end-artery anatomy—is further reduced.

Oedema. Fluid resuscitation, capillary leak, and organ dysfunction often produce peripheral oedema. Swollen tissues are more susceptible to pressure damage.

Altered consciousness. Sedation removes the protective responses that might prompt movement or position adjustment in an alert patient.

Prolonged procedures. Surgery, imaging, and bedside procedures may keep patients in fixed positions for extended periods.

Nutritional compromise. Critical illness affects nutritional status, impairing the tissue repair mechanisms that might otherwise limit pressure injury progression.

Extended length of stay. The longer a patient remains in ICU, the longer their heels are exposed to continuous risk.

Any one of these factors increases pressure ulcer risk. In combination, they create conditions where heel damage becomes highly likely without active prevention.

The heels are vulnerable from the moment of ICU admission.

Pressure damage can begin with sustained pressure. Biomechanics tells us that even low pressures sustained for a long period of time are as destructive as very high pressures for a short period of time. When sustained for long enough, any pressure can be significant. The clock starts ticking from the moment the patient becomes immobile.

Consider a typical ICU admission pathway:

Emergency department: Patient on trolley, heels resting on mattress, awaiting assessment and stabilisation

Imaging: Transfer to CT scanner, heels on imaging table for 30-60 minutes

Theatre (if surgical): Heels on operating table for the duration of surgery, potentially several hours

ICU admission: Transfer to ICU bed, heels now on ICU mattress

By the time a patient reaches the ICU bed, their heels may already have experienced several hours of sustained pressure across multiple surfaces and settings. The damage process may already have begun before ICU-specific prevention measures are considered. This argues for implementing heel protection as early in the pathway as possible—ideally in the emergency department or pre-operatively—rather than waiting until ICU admission.

Prophylactic offloading is more effective than reactive treatment.

The case for prophylactic heel offloading rests on a simple observation: preventing pressure injury is far easier than treating one.

Once a pressure ulcer develops wound care becomes necessary, adding to nursing workload. Healing takes time—weeks or months in significant injuries and evidence shows that we'll need pressure offloading To accomplish healing We do know that the structural integrity of the skin is compromised, and that it is greatly increasing the risk of ulceration in the future. Ulceration can lead to other complications including infection and osteomyelitis. Now, inevitably, the patient's rehabilitation and discharge are delayed and healthcare costs escalate substantially. Prevention avoids all of this. A patient whose heels remain intact throughout their ICU stay doesn't need wound care, doesn't face healing delays, and doesn't accrue the additional costs and complications that pressure injuries generate.

The evidence supports this approach. Studies implementing systematic heel offloading in critical care settings report substantial reductions in heel pressure injury rates—75% or greater in some implementations.

The 2025 International Pressure Injury Guideline recommends that heels be "fully free from contact with the support surface." This recommendation applies to all at-risk patients, with ICU patients among the highest-risk category.

What effective ICU heel protection looks like.

Effective heel protection in intensive care requires addressing the specific challenges of the ICU environment: Complete offloading is necessary, not just pressure reduction. Given the multiple compounding risk factors in ICU patients, pressure reduction is often insufficient. The goal should be heel floating—complete elimination of contact between the heel and any surface. We mentioned above there is no guaranteed safe level of pressure other than zero.

Reliable positioning is required. Devices must maintain the heel in an offloaded position despite patient movement, turning, and the inevitable repositioning that ICU care requires. Pillows that shift and allow heel contact offer inadequate protection.

The PRAFO range is available for adult, infant, paediatric and, as shown here, bariatric patients.

Compatibility with other ICU equipment should be a requirement. Heel protection devices must work alongside sequential compression devices, arterial and venous lines, and other equipment commonly used in critical care.

Durability for extended use should be a requirement. ICU stays can last days to weeks. Devices must withstand continuous use over this period without losing effectiveness.

Ease of skin inspection is essential just as regular skin assessment is essential. Devices that make inspection difficult—or that must be fully removed and refitted for each assessment—create barriers to monitoring.

The Prafo range addresses these requirements through its design:characteristics that ensure complete heel suspension through an engineered metal structure, stable positioning that doesn't rely on pillows or foam that can shift, and easy access for skin inspection without compromising protection.

Implementation requires protocol integration.

Successful heel protection in ICU isn't just about having the right devices available. It requires integrating protection into standard care protocols.

Heel protection should be part of the standard ICU admission process—implemented automatically for all patients meeting risk criteria, not left to individual clinical discretion. Protocols should specify when heel protection is implemented. "Within 4 hours of admission" is better than "when convenient." Ideally, protection should be in place before the patient reaches the ICU bed—applied in the emergency department or pre-operatively.

Heel protection status should be documented and visible—on the bedside chart, in the nursing handover, and in the medical record. What isn't documented often isn't done. It needs to be easy and convenient for busy people to take action. Regular skin inspection should be mandated and recorded. The frequency will depend on patient acuity, but daily inspection is a minimum for most ICU patients.

When patients transfer out of ICU—to step-down units, wards, or rehabilitation—heel protection status should be explicitly communicated so that the protection that worked in ICU should continue in the receiving unit.

The economic case is compelling.

For healthcare administrators and budget holders, the economics of pressure ulcer prevention in ICU are stark.

A single hospital-acquired pressure ulcer adds substantially to the cost of care:

- Direct wound care costs (dressings, nursing time, specialist input)

- Extended length of stay

- Potential surgical intervention for severe injuries

- Litigation risk

Estimates vary, but the per-ulcer cost runs into thousands of pounds. For heel ulcers specifically, the anatomical challenges of the heel site can make healing prolonged and costly. Against this, prophylactic offloading devices represent a modest investment. When a single prevented pressure ulcer saves more than the cost of providing protection to multiple patients, the return on investment is clear.

Beyond direct costs, hospital-acquired pressure ulcers affect quality metrics, patient satisfaction, and institutional reputation. Preventing them aligns with broader quality improvement goals.

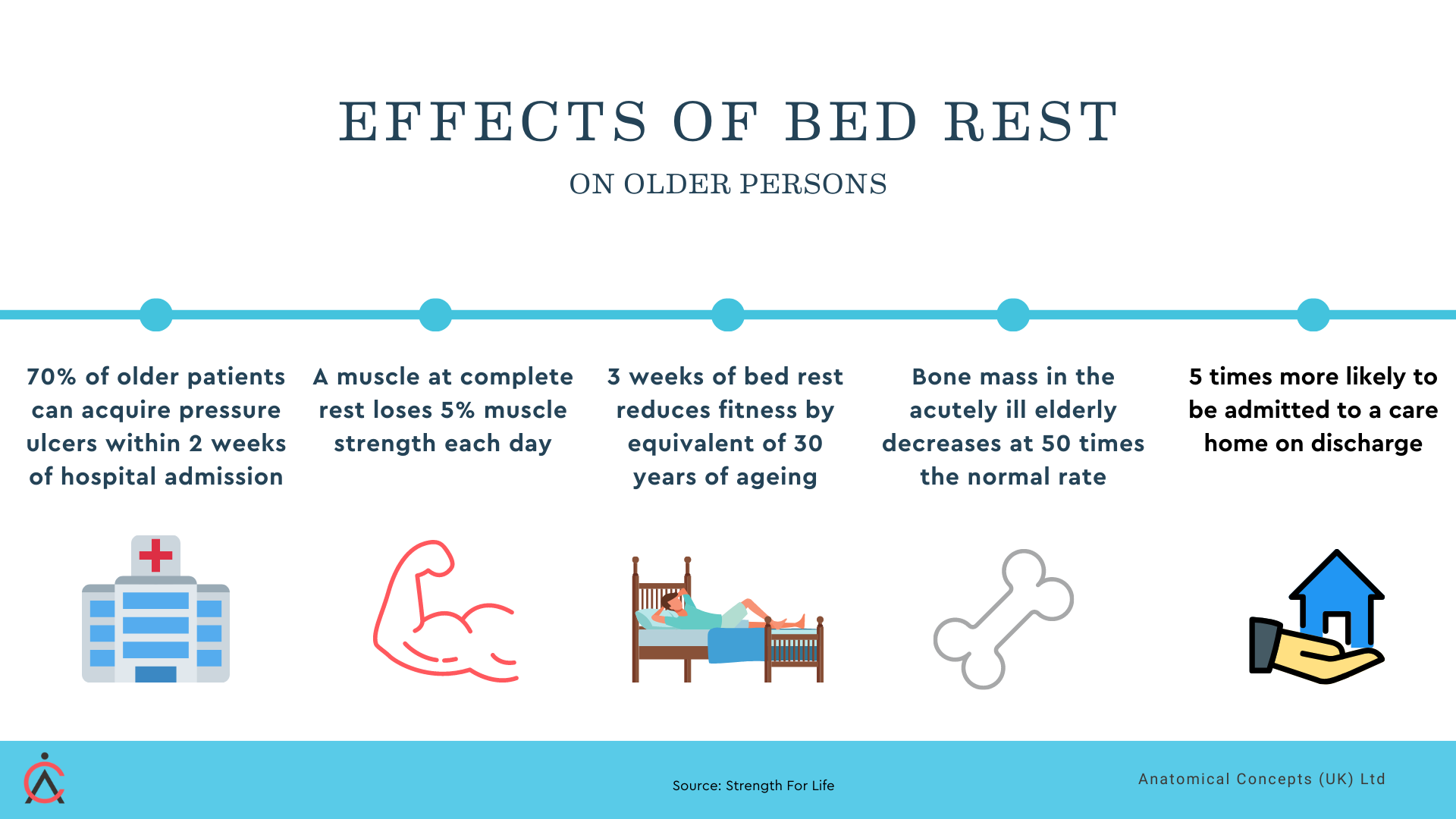

Prolonged bed rest has significant implications for continuity of care.

Practical steps for ICU teams.

1. Audit current practice. What proportion of ICU patients currently receive heel offloading? What devices are in use? What is the heel pressure ulcer incidence rate? Understanding baseline performance guides improvement efforts.

2. Select appropriate devices. Evaluate heel protection options against ICU-specific requirements: complete offloading, reliable positioning, compatibility with other equipment, durability, and ease of inspection.

3. Integrate into admission protocols. Make heel protection a standard component of ICU admission, applied automatically based on risk criteria rather than requiring individual clinical decision-making for each patient.

4. Specify implementation timing. Define when protection should be in place—ideally within hours of admission, or earlier if pre-operative or emergency department application is feasible.

5. Train staff. Ensure all ICU nursing staff can correctly apply and assess heel protection devices. Include heel protection in ICU orientation and competency assessment.

6. Monitor and feedback. Track heel pressure ulcer rates as a quality metric. Feed results back to clinical teams. Celebrate improvements; investigate failures.

Prevention is easier than treatment.

Intensive care patients face enough challenges without adding preventable heel damage to the list. The heels are vulnerable from the moment of ICU admission—often from before admission. Protection that waits until skin changes are visible has already failed at prevention.

Prophylactic heel offloading, implemented early and maintained throughout the ICU stay, prevents injuries that would otherwise require weeks or months of treatment. The evidence supports it. The economics favour it. The 2025 guidelines recommend it.

The question isn't whether to implement heel protection in ICU. It's how quickly and how consistently it can be applied to every patient who needs it.