Is the Autonomic Nervous System Ever Truly "In Balance"?

Why the seesaw model is misleading — and what it means for rehabilitation

Introduction to our article on the notion of a balanced autonomic nervous system

If you have been reading about the autonomic nervous system — perhaps because you live with a spinal cord injury, or you work with people who do — you will almost certainly have encountered the idea of "autonomic balance." The image is seductive: sympathetic on one side, parasympathetic on the other, and health is achieved when the two sit neatly level, like a set of scales in equilibrium.

It is a useful teaching shorthand. It is also, as modern physiology has demonstrated over the past three decades, an oversimplification that can actually mislead both clinicians and patients.

The fundamental question is this: does the autonomic nervous system ever truly achieve "balance" — and if not, what should we be aiming for instead? The answer has direct implications for how we think about autonomic dysfunction after spinal cord injury and for emerging interventions such as transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) that aim to improve autonomic regulation.

Introducing the autonomic nervous system

Before we challenge the "balance" idea, it helps to understand what the autonomic nervous system actually is — particularly if you are encountering these concepts for the first time.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is the part of your nervous system that runs in the background, regulating the functions you do not have to think about: heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, breathing rate, body temperature, and bladder function. It operates largely below conscious awareness, adjusting these processes moment by moment in response to what your body needs. It's like the operating system in your computer. Essential for everything that happens, even though we're not necessarily thinking about it too much from moment to moment

It has two main branches:

- The sympathetic nervous system prepares you for action. It increases heart rate, raises blood pressure, diverts blood to the muscles, and mobilises energy stores. This is often called the "fight-or-flight" response, though it is active to some degree all the time — not just in emergencies. When we perceive a stressor, this is the system that is activated.

- The parasympathetic nervous system promotes conservation and recovery. It slows the heart, stimulates digestion, and supports restorative processes. The vagus nerve — the longest cranial nerve in the body, running from the brainstem to the abdomen — is the main parasympathetic highway, and it plays a central role in the story that follows.

Most organs receive input from both branches, and the interplay between them determines how each organ functions at any given moment. So far, so straightforward. The question is whether this interplay is best described as "balance" — and that is where things get interesting.

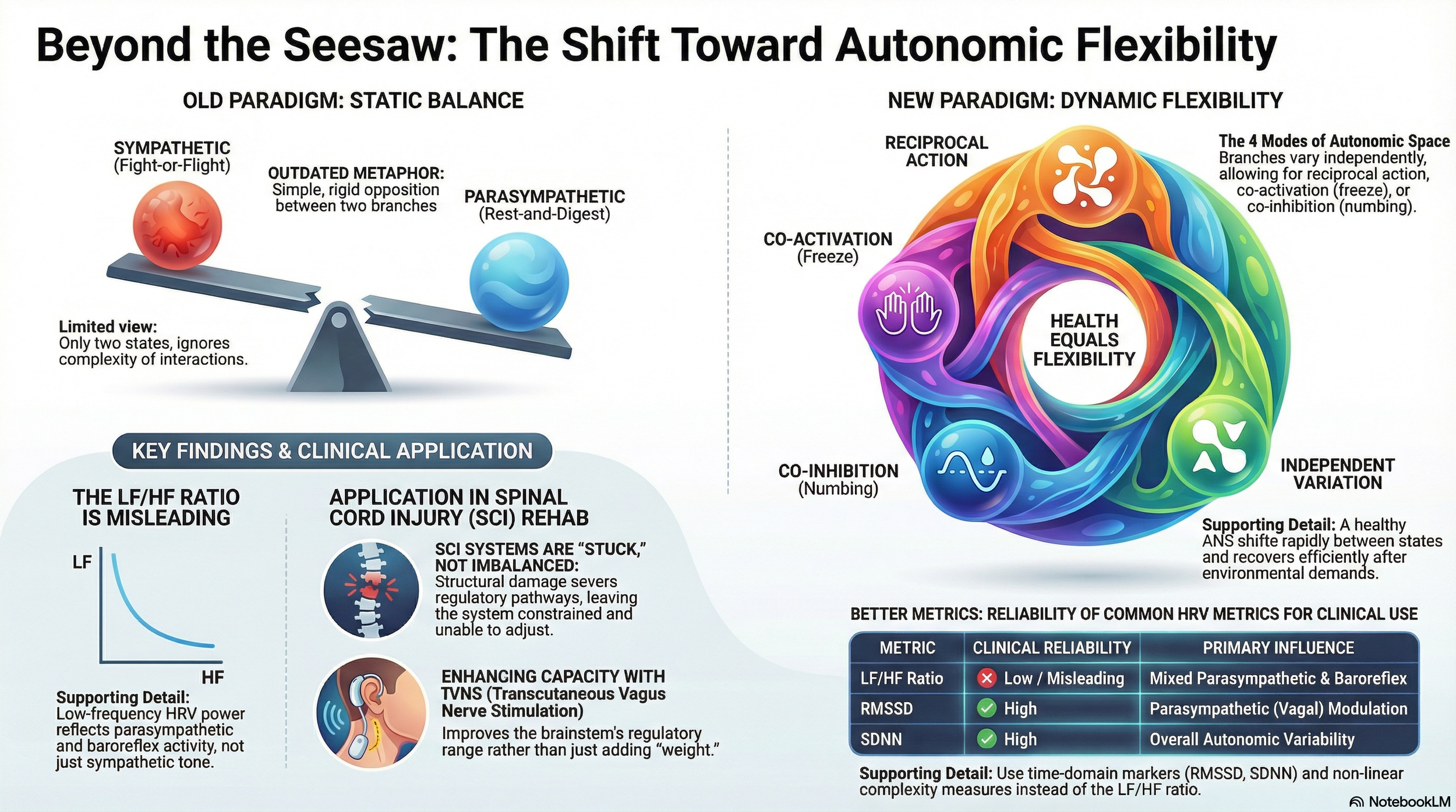

The textbook model: a seesaw with two ends

The standard explanation goes like this. The sympathetic nervous system prepares you for action — heart rate up, blood pressure up, energy mobilised. You are ready to "fight or flight". The parasympathetic system does the opposite — heart rate slows, digestion is active, and energy is conserved. Health is a matter of keeping these two branches in appropriate proportion.

This model captures something real. Many organs do receive dual innervation with opposing effects. The heart is the clearest example: sympathetic stimulation increases heart rate; vagal (parasympathetic) stimulation decreases it. But the seesaw image suggests that these two branches always move in opposite directions — one goes up, the other comes down — and that there exists some ideal midpoint where they are "balanced."

The research tells a different story.

Four autonomic modes, not two

In 1991, Gary Berntson and colleagues at Ohio State University published a paper that fundamentally challenged the seesaw model. Their work, published in Psychological Review, introduced what they called the "doctrine of autonomic space" — the idea that sympathetic and parasympathetic activity can vary independently of one another.

This matters enormously, because independent variation produces not two possible states but at least four:

- Reciprocal sympathetic activation — sympathetic up, parasympathetic down. This is the classic "fight-or-flight" response: heart pounding, blood redirected to muscles, digestion paused.

- Reciprocal parasympathetic activation — parasympathetic up, sympathetic down. The classic "rest-and-digest" state: heart rate low, digestion active, energy being conserved.

- Co-activation — both branches are active simultaneously. This might seem contradictory, but it occurs more often than the seesaw model would predict. The "freeze" response is one example. Another is certain phases of digestion, where heart rate rises as gut motility increases.

- Co-inhibition — both branches withdrawn. This is seen in some forms of emotional numbing and in certain disease states, where the autonomic nervous system appears to disengage from its regulatory role.

In a follow-up study (Berntson et al., 1994, Psychophysiology), the researchers exposed healthy volunteers to laboratory stressors and observed all four modes of autonomic response, and the pattern varied across individuals and across tasks. The two-ended seesaw simply cannot account for what was happening.

KEY POINT: The sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system can vary independently. A healthy person routinely uses at least four modes of autonomic response — not two. The "seesaw" is a teaching shorthand, not a physiological reality.

The problem with measuring "balance": why the LF/HF ratio is misleading

If you have had your heart rate variability (HRV) assessed — perhaps using a consumer device or in a clinical setting — you may have been told about the LF/HF ratio. This is a so-called frequency domain measure. This metric divides the low-frequency power of your heart rate signal (around 0.04–0.15 Hz) by the high-frequency power (0.15–0.40 Hz) and presents the result as a measure of "sympathovagal balance."

The idea, promoted by a landmark 1996 Task Force guideline from the European Society of Cardiology, was that the LF component reflects sympathetic activity while the HF component reflects parasympathetic activity. Divide one by the other to get a balance score.

Elegant. Intuitive. And, as subsequent research has shown, deeply problematic.

The critical issue is that the LF component does not reliably reflect sympathetic activity. In 1997, Dwain Eckberg published a paper in Circulation titled "Sympathovagal balance: a critical appraisal," warning that the concept was being applied far beyond what the evidence supported. In 2013, George Billman wrote even more directly in Frontiers in Physiology: "The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance."

That same year, Reyes del Paso and colleagues showed that low‑frequency power reflects substantial contributions from parasympathetic activity and baroreflex modulation, with only a limited, context‑dependent contribution from purely sympathetic input. In other words, LF power is primarily a parasympathetic and baroreflex phenomenon — not a sympathetic one. Dividing it by HF power does not give you a meaningful "balance" score.

For example, investigators have reported paradoxical increases in the LF/HF ratio after combined autonomic blockade and decreases during exercise, even though sympathetic activation is clearly dominant, behaviours that are inconsistent with a simple ‘balance’ metric. These are not the behaviours of a reliable balance indicator.

KEY POINT: The LF/HF ratio, widely marketed as a measure of autonomic "balance," is now considered misleading by many leading researchers. The low-frequency component of HRV does not reliably reflect sympathetic activity. If you are using LF/HF as a clinical metric, the research now suggests you should interpret it with considerable caution.

Autonomic "tone" rather than "balance"

Physiology textbooks have long used the term autonomic tone to describe the continuous baseline activity of each branch, and this concept reveals another reason the "balance" metaphor breaks down. Autonomic tone differs by organ.

Consider: at rest, the heart is predominantly under parasympathetic control. The vagus nerve actively slows it from its intrinsic rate of roughly 100 beats per minute down to the 60–80 bpm we recognise as a typical resting heart rate. Meanwhile, the vasculature — the blood vessels — is predominantly under sympathetic tone. Smooth muscle in blood vessel walls is kept mildly constricted by continuous sympathetic discharge, with negligible parasympathetic input.

So even in a healthy person sitting quietly, different organs are biased toward different branches of the autonomic nervous system. There is no single, system-wide set point at which both branches are equal. The question "Is the ANS in balance?" is rather like asking "Is the temperature in your house balanced?" when the kitchen is warm, the bedroom is cool, and the bathroom is somewhere in between. The question itself reveals a misunderstanding of how the system is organised.

A better concept: autonomic flexibility

If "balance" is the wrong word, what is the right one?

The answer that has emerged from three decades of research is autonomic flexibility — the capacity of the autonomic nervous system to shift fluidly between states in response to changing demands, and to recover efficiently afterwards.

Julian Thayer and Richard Lane formalised this idea in their neurovisceral integration model, first published in the Journal of Affective Disorders in 2000. They proposed that the prefrontal cortex exerts top-down inhibitory control over subcortical threat circuits, and that this regulatory capacity is reflected in heart rate variability. High HRV, in this framework, is not about "balance" — it is about flexibility. It indicates an autonomic nervous system that responds rapidly and appropriately to environmental demands and then returns to baseline.

In a 2012 meta-analysis published in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, Thayer and colleagues demonstrated, using neuroimaging, that HRV correlates with activity in a network of brain regions — the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, insula, and amygdala — involved in autonomic regulation, emotional processing, and executive function. Reduced HRV was associated with reduced prefrontal activity and heightened amygdala reactivity.

This means that a healthy autonomic nervous system is not one sitting perfectly still on a balanced seesaw. It is one that can move rapidly across the four modes Berntson described — activating, inhibiting, co-activating, and recovering — in patterns that are appropriate to the situation. Health is about range of movement, not about a static position.

KEY POINT: Modern autonomic science has shifted from "balance" to "flexibility" as the marker of health. A healthy ANS is not one that sits still in the middle — it is one that can move rapidly and appropriately between states, and recover efficiently. This is what heart rate variability actually measures: the capacity for dynamic regulation.

The polyvagal perspective adds another layer

Stephen Porges' Polyvagal Theory, first proposed in 1995, further challenges the simple balance concept by arguing that the parasympathetic side of the equation is itself not a single system.

Porges proposed that the vagus nerve contains two functionally distinct circuits with different evolutionary origins. The phylogenetically newer ventral vagal complex — associated with myelinated vagal fibres, the nucleus ambiguus, and connections to the muscles of the face and head — supports social engagement, flexible heart-rate modulation, and calm, connected states. The older dorsal vagal complex — associated with unmyelinated fibres and the dorsal motor nucleus — is linked to immobilisation, shutdown, and the "freeze" response seen in extreme threat.

In this framework, health is not about balancing sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. It is about the capacity to engage the ventral vagal system for social interaction, to shift into sympathetic activation when genuine danger requires it, and to avoid the kind of dorsal vagal shutdown that represents a last-resort survival mechanism.

The hierarchy matters: social engagement first, fight-or-flight when necessary, shutdown only under extreme duress.

I should be transparent with you: Polyvagal Theory has generated considerable scientific debate. Paul Grossman, Edwin Taylor, and colleagues have published detailed critiques questioning the evolutionary claims, the neuroanatomical specificity of the two vagal circuits, and whether respiratory sinus arrhythmia (a key marker in the theory) reliably indexes cardiac vagal tone without accounting for respiratory parameters. Their 2023 paper in Biological Psychology is titled, without ambiguity, "Why we must reject Polyvagal Theory as untenable."

Porges has responded to these criticisms, arguing that the critiques conflate anatomical detail with functional organisation.

Where does this leave us? The neuroanatomical existence of multiple vagal pathways is well‑established, and the clinical intuition that vagal regulation is not a single, undifferentiated process fits with the broader shift from ‘balance’ to ‘flexibility’.

What remains contested are Polyvagal Theory’s specific evolutionary claims and its mapping of particular psychological ‘states’ onto distinct vagal circuits. The summary is this: Polyvagal Theory offers a clinically useful framework for understanding autonomic states, while some of its underlying scientific claims await further resolution.

What this means for spinal cord injury rehabilitation

For people living with spinal cord injury, the shift from "balance" to "flexibility" is not merely academic. It is the most accurate way to understand what has actually happened to their autonomic nervous system.

Spinal cord injury, particularly at or above the sixth thoracic segment (T6), does not simply "tip the seesaw" in one direction. T6 marks the approximate upper boundary of the major splanchnic sympathetic outflow — the sympathetic pathways that control the large abdominal blood vessel network. Injuries at or above this level disrupt descending sympathetic pathways to the heart and major vasculature, severing the connections that allow the brainstem to coordinate autonomic responses across the body.

The consequences are well-documented. Andrei Krassioukov, who chairs the International Autonomic Standards Committee of ASIA and ISCoS, has spent more than twenty years researching autonomic dysfunction after SCI. The International Standards to document remaining Autonomic Function after Spinal Cord Injury (ISAFSCI), published by Krassioukov and colleagues in the Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine in 2012, provides a standardised framework for assessing which autonomic functions remain — and which have been lost.

The three cardinal cardiovascular consequences are familiar to anyone working in SCI rehabilitation:

1. Orthostatic hypotension — Loss of sympathetic vasoconstrictor control means the body cannot compensate for the gravitational redistribution of blood when moving from lying down to sitting or standing. Blood pools in the abdomen and legs, blood pressure drops, and cerebral perfusion falls.

2. Autonomic dysreflexia — A potentially dangerous condition seen in injuries at or above T6. Noxious stimuli below the injury level — a full bladder, tight clothing, a developing pressure ulcer — trigger massive, uncontrolled sympathetic discharge in the isolated spinal cord. This produces severe hypertension that the brainstem cannot dampen because the descending inhibitory connections have been severed.

3. Reduced heart rate variability — The combined effects of impaired sympathetic outflow and altered vagal-sympathetic integration produce markedly reduced HRV. This is not simply "more parasympathetic" or "more sympathetic." It is a loss of the dynamic interplay between both branches.

A 2013 systematic review by West and colleagues reported that the degree of autonomic completeness is more closely associated with cardiovascular dysfunction after SCI than conventional neurological completeness classifications alone. Two individuals with the same neurological level and the same ASIA classification can have very different cardiovascular autonomic profiles, depending on the extent of damage to autonomic pathways.

The critical insight is this: the autonomic system after high-level SCI is not imbalanced. It is stuck.

The system has lost the structural connections required for flexible, coordinated regulation. It cannot shift appropriately between states — not because a dial has been turned too far in one direction, but because the wiring that enables adjustment has been physically interrupted.

This is fundamentally different from, say, chronic stress in an able-bodied person, where the hardware is intact but overloaded. In SCI, the hardware is structurally compromised. The system is constrained, with a narrowed repertoire of available autonomic states.

KEY POINT: After spinal cord injury, the autonomic nervous system is not "imbalanced" — it is structurally constrained. The system cannot flexibly adjust because the pathways that enable adjustment have been physically severed. This distinction matters for understanding the rationale for interventions aimed at restoring regulatory capacity.

Why this reframing strengthens the case for tVNS

This reframing — from "balance" to "flexibility" — actually strengthens the clinical rationale for transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation rather than weakening it. Here is why.

The old framing would say: "tVNS adds parasympathetic tone to restore sympathovagal balance."

This is mechanistically simplistic. It implies that tVNS is merely placing weight on one side of the seesaw.

The more accurate framing: tVNS drives afferent vagal input — sensory signals travelling inward — through the auricular branch of the vagus nerve into the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brainstem. The NTS is the central hub of the autonomic network. From there, signals project to the locus coeruleus (releasing norepinephrine, involved in arousal and attention), the raphe nuclei (releasing serotonin, involved in mood and pain modulation), and higher brain regions, including the insula and anterior cingulate cortex.

Neuroimaging evidence supports this pathway. Badran and colleagues published a concurrent tVNS/fMRI study in Brain Stimulation (2018) demonstrating that auricular vagus nerve stimulation activates brain regions involved in autonomic regulation, interoception, and executive control — consistent with modulation of the central autonomic network rather than simply boosting vagal efferent output to the heart.

In practical terms, this means tVNS does not simply "add parasympathetic weight to the scale." It enhances the regulatory capacity of the brainstem integration centres that coordinate autonomic output across the entire body. The goal is to improve the range and speed of autonomic adjustments — to expand the repertoire of autonomic states available to a system that injury or disease has constrained.

Clancy and colleagues (2014) demonstrated in healthy volunteers that auricular tVNS significantly suppressed sympathetic nerve activity — measured directly via microneurography — with a reduction of approximately 50% in burst frequency during stimulation. And in a landmark 2025 paper published in Nature, Ganzer and colleagues showed that closed-loop vagus nerve stimulation paired with rehabilitation led to significant improvements in arm and hand function in people with chronic, incomplete cervical SCI. While this study used implanted rather than transcutaneous VNS, both approaches engage vagal afferents projecting to the nucleus tractus solitarius, and the trial supports the broader principle that appropriately timed vagal stimulation paired with rehabilitation can enhance functional recovery after SCI.

For clinician-facing materials, the language of *restoring autonomic flexibility and regulatory capacity* is both more accurate and more compelling than the language of restoring autonomic balance. It resonates with what the evidence actually shows and avoids the oversimplified seesaw metaphor that physiologists have been moving away from for the past 3 decades.

What should we actually measure?

If the LF/HF ratio is unreliable, what should clinicians and patients look at instead? The answer involves several complementary metrics, each capturing a different aspect of autonomic function.

Time-domain measures

RMSSD (Root Mean Square of Successive Differences) — This captures beat-to-beat heart rate variability and is the primary time-domain marker of vagal (parasympathetic) modulation. Lower values indicate reduced vagal influence on heart rate.

SDNN (Standard Deviation of Normal-to-Normal intervals) — This captures overall variability across the entire recording, reflecting the contribution of both autonomic branches. In 24‑hour recordings, low SDNN values are associated with markedly increased cardiovascular risk and post‑infarct mortality, with values under roughly 50 milliseconds often used as a pragmatic threshold for severely reduced variability in older studies. The critical distinction: RMSSD captures short-term, beat-to-beat vagal modulation. SDNN captures the bigger picture of both branches operating over time. You can have adequate RMSSD with reduced SDNN, or vice versa. They are complementary, not interchangeable.

Non-linear measures: capturing complexity

Non-linear methods capture something that time-domain measures alone cannot: the *complexity* of autonomic regulation. A healthy autonomic nervous system does not simply vary a lot; it varies in complex, non-random, fractal-like patterns. Loss of this complexity — not just loss of variability — is a marker of disease.

Sample Entropy quantifies the unpredictability of the heart rate time series. Higher values indicate more complex, adaptive regulation. Reduced sample entropy is associated with heart failure, diabetes, and other disease states.

DFA α1 captures fractal scaling in the heart rate signal: values around 1.0 are typical of healthy, fractal‑like variability, whereas shifts toward more random (≈0.5) or more rigid, highly correlated patterns (≈1.5) have been linked to various disease states.

As Shaffer and Ginsberg noted in their comprehensive 2017 review in Frontiers in Public Health, a healthy heart does not beat with metronomic regularity. It exhibits complex oscillations that allow rapid cardiovascular adjustment to changing demands. This is autonomic flexibility expressed at the level of individual heartbeats.

KEY POINT: For tracking autonomic function, RMSSD and SDNN provide more reliable and better-understood information than the LF/HF ratio. Non-linear measures like sample entropy and DFA capture the *complexity* of regulation — arguably the most clinically relevant dimension, and the one most aligned with the concept of autonomic flexibility. Serial measurements over weeks to months are more informative than any single "balance" score.

The bigger picture

Many years ago, my mentor introduced me to the concept of a useful lie. As a university teacher, I would quite often paraphrase a technical and detailed lecture by saying to my students that “everything I'm about to tell you is a lie, but likely to be a useful lie”. Simplification can sometimes be useful. I've been guilty in the past of teaching the concept of autonomic balance to stressed executives. They could easily learn to adjust their breathing, focus on their heart, and indirectly use the vagus nerve to bring their autonomic system into balance, thereby dissipating a stressful state. What everyone wants: Techniques That Work - We want to know that something is safe and it's effective. In this article, we've left behind the simple concept of balance and explored something that might just lead to new insights helpful in rehabilitation.

A healthy autonomic nervous system is not balanced. It is dynamically responsive — constantly shifting its output across organs and across time, adjusting to posture, activity, digestion, emotion, temperature, and a thousand other demands. The metaphor is not a set of scales sitting level. It is more like an orchestra, with multiple instruments playing independent parts that together produce coordinated music. Health is not about every instrument playing at the same volume. It is about the conductor's ability to bring the right instruments in at the right time.

Disease and injury do not tip a scale. They narrow the repertoire — silencing instruments, breaking the conductor's connection to certain sections of the orchestra. The music becomes simpler, more rigid, less responsive to what the moment demands.

That is what tVNS can begin to address. Not by adding volume to one side of a seesaw, but by restoring communication with the conductor — the brainstem integration centres that coordinate the entire autonomic response.

For those of us working in rehabilitation, this is the language that matters. Not balance, but flexibility. Not equilibrium, but adaptive capacity. Not a static set-point, but the dynamic range of responses that allows a person to meet the demands of daily life.

If this topic is relevant to you — whether you are living with a spinal cord injury, caring for someone who is, or working as a clinician in this field — we would welcome the opportunity to discuss how transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation might fit into your rehabilitation programme. Contact us to arrange a conversation.

References

Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Quigley, K. S. (1991). Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint. Psychological Review, 98(4), 459–487.

Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., Quigley, K. S., & Fabro, V. T. (1994). Autonomic space and psychophysiological response. Psychophysiology, 31(1), 44–61.

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. (1996). Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. European Heart Journal, 17(3), 354–381.

Eckberg, D. L. (1997). Sympathovagal balance: A critical appraisal. Circulation, 96(9), 3224–3232.

Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 201–216.

Claydon, V. E., & Krassioukov, A. V. (2006). The clinical problems in cardiovascular control following spinal cord injury: An overview. Progress in Brain Research.

Grossman, P., & Taylor, E. W. (2007). Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 263–285.

Krassioukov, A., et al. (2012). International Standards to document remaining Autonomic Function after Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 35(4), 201–210.

Thayer, J. F., Ahs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(2), 747–756.

Billman, G. E. (2013). The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Frontiers in Physiology, 4, 26.

Reyes del Paso, G. A., Langewitz, W., et al. (2013). The utility of low frequency heart rate variability as an index of sympathetic cardiac tone: A review with emphasis on a reanalysis of previous studies. Psychophysiology, 50(5), 477–487.

West, C. R., et al. (2013). Systematic review of the relationship between cardiovascular function and neurological and autonomic completeness of injury.

Clancy, J. A., et al. (2014). Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in healthy humans reduces sympathetic nerve activity. Brain Stimulation, 7(6), 871–877.

Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258.

Badran, B. W., Austelle, C. W., et al. (2018). Neurophysiologic effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) via electrical stimulation of the tragus: A concurrent taVNS/fMRI study and review. Brain Stimulation, 11(3), 492–500.

Grossman, P., Taylor, E. W., et al. (2023). Why we must reject Polyvagal Theory as untenable: An international expert evaluation of basic premises. Biological Psychology, 176, 108539.

Ganzer, P. D., et al. (2025). Closed-loop vagus nerve stimulation aids recovery from spinal cord injury. Nature, 643(8073), 1030–1036.

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318.

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143.