How to Choose a Stimulator for Denervated Muscle: What Actually Matters

If you've determined that you need electrical stimulation for denervated muscles, the next question is obvious: which device should you choose? This is where many people become confused — and understandably so. The market is flooded with electrical stimulation devices, most of which cannot help denervated muscles, and the technical specifications can be bewildering even for clinicians, let alone someone navigating this for the first time after a life-changing injury.

In my experience, the confusion isn't really about the number of options. It's about how devices that look similar on the outside — a box, some wires, a pair of electrodes — can be fundamentally different on the inside. A TENS unit from a pharmacy or bought online, and a specialised denervated muscle stimulator may appear related, but they are designed for entirely different physiological purposes. Choosing the wrong one isn't just a waste of money; it means lost time during a period when early intervention matters most.

It's worth pausing to consider why this matters so much. When a muscle loses its nerve supply, it doesn't simply sit idle waiting for treatment. Without regular neural input, the muscle fibres begin to atrophy — shrinking and weakening progressively. Over time, the natural contractile tissue is gradually replaced by collagen and fat, and once this process is sufficiently advanced, it cannot be reversed. The muscle becomes a mass of tissue structurally incapable of functioning as a muscle. The consequences extend beyond the muscles themselves: loss of muscle bulk increases the risk of pressure ulcers, impairs circulation, and creates a generally poor trophic situation that affects long-term health. If reinnervation does eventually occur — as it may with some peripheral nerve injuries or after surgery — there must be viable muscle tissue for the nerve to reconnect with. Appropriate electrical stimulation, started early, can preserve that tissue and maintain its quality. This is why the choice of equipment is not merely a purchasing decision. It is, in a very real sense, a clinical one.

In this article, I'll explain what features actually matter for denervated muscle stimulation, why most devices on the market are unsuitable, and how to evaluate your options. My goal is to help you make an informed decision, understanding both what's essential and what's marketing noise. I'll draw on the published research that underpins this field — particularly the work of Helmut Kern, Ugo Carraro, and their colleagues in the European RISE study — and on our own practical experience at Anatomical Concepts working with clients who use this technology at home.

Why Denervated Muscles Need Different Equipment

Before we get into device specifications, it's worth understanding *why* denervated muscle requires fundamentally different stimulation. This isn't a matter of ‘turning up the dial’ on a standard device. The underlying physiology is completely different.

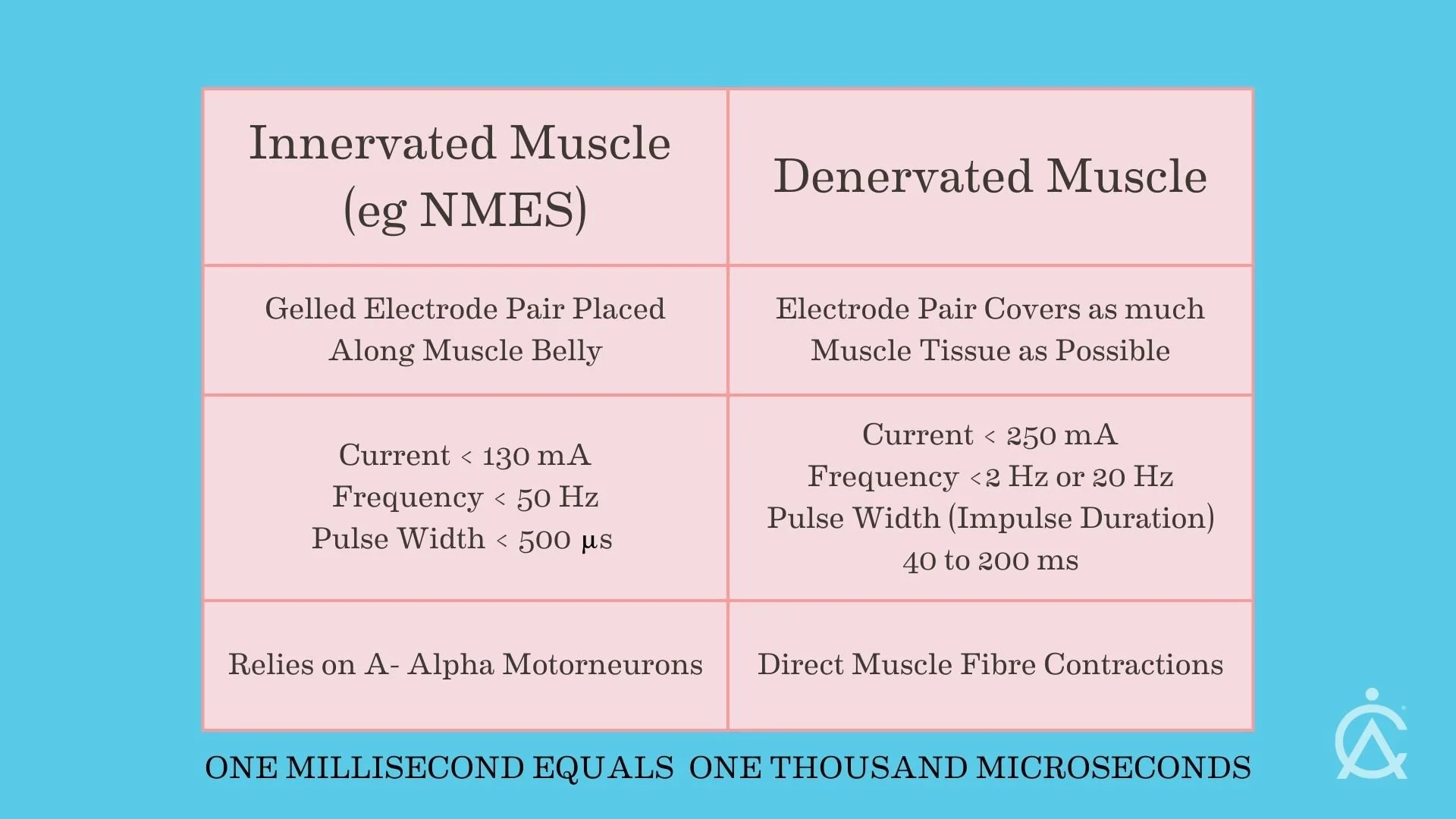

In a healthy nerve-muscle system, electrical stimulation activates the motor nerve, which then triggers all the muscle fibres in that motor unit to contract. This is efficient because nerves have very low excitation thresholds — a brief electrical pulse of less than one millisecond is sufficient to trigger an action potential that propagates along the nerve to the muscle. Practically all established clinical applications of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) rely on this indirect pathway: stimulating the nerve activates the muscle.

Comparing Stimulation Parameters

When the nerve is damaged or destroyed, this pathway ceases to exist. The neuromuscular junction degenerates, motor units disintegrate, and the only way to make the muscle contract is by directly depolarising the membrane of each individual muscle fibre.

This is a fundamentally harder task. Muscle fibre membranes have much higher chronaxie (Chronaxie is a way of describing how easily a nerve or muscle responds to an electrical signal) values than nerve tissue, approximately 10 to 100 milliseconds compared with 0.05 to 0.7 milliseconds for intact nerve (Kern and Carraro, 2014). The resting membrane potential of denervated fibres is reduced, making them less excitable. And as denervation progresses, connective tissue and fat infiltrate the muscle, creating resistance that diverts current away from the remaining viable fibres.

The practical consequence is striking. A recent comprehensive review by Chu and colleagues (2025) in *Artificial Organs* confirmed that denervated muscle requires approximately one thousand times higher stimulation thresholds than indirect stimulation via intact lower motor neurons. That figure bears repeating: one thousand times. No amount of adjustment on a standard NMES device can bridge that gap. The device must be designed from the ground up for this purpose.

KEY POINT: The difference between stimulating innervated and denervated muscle is not one of degree — it's a difference in kind. Standard devices stimulate nerves which then generates a muscle contraction; denervated muscle stimulators must directly activate muscle fibres. These are fundamentally different tasks requiring fundamentally different equipment.

The Essential Technical Requirements

With that physiology in mind, let me set out the non-negotiable technical requirements for a denervated muscle stimulator. If a device fails any one of these criteria, it cannot do the job, regardless of how sophisticated its other features may be.

Long Pulse Durations

This is the single most important specification, and the one that eliminates most devices on the market immediately. To directly depolarise the membranes of denervated muscle fibres, you need pulse widths of 100 to 200 milliseconds. The protocols established by the European RISE study used pulse widths of 120 to 200 milliseconds for initial twitch-phase training, gradually reducing to 40 to 50 milliseconds as excitability improved and tetanic contractions became achievable (Kern et al., 2002; Kern and Carraro, 2014).

Most consumer and clinical electrical stimulation devices have maximum pulse widths of 0.5 to 1 millisecond — that is, 100 to 400 times shorter than what a denervated muscle requires. If a device's maximum pulse width is less than 1 millisecond, typically expressed as 1,000 microseconds in device specifications, it is physiologically incapable of stimulating denervated muscle. This single specification eliminates the vast majority of currently available devices.

Adequate Current Output

Sufficient current must reach the muscle fibres to cause contraction, and the current needs to penetrate through skin and subcutaneous tissue to reach deep muscle fibres. For denervated muscle stimulation, you may need more current than that available from devices intended for neuromuscular electrical stimulation. The RISE Stimulator, for example, can deliver 250 mA. Certainly, in cases where such currents are needed, particular caution should be taken, but if this current is available, it opens treatment to many more people who may have had no prior treatment for muscle denervation for a decade or more.

Most consumer devices limit current output to 80 to 130 milliamperes for safety reasons, to reduce the risk of skin burns with standard small electrodes. This is entirely appropriate for nerve stimulation, where lower currents are effective, but it is insufficient for many denervated muscle applications. The original Den2x stimulator developed for the RISE study could deliver up to 300 milliamps; the current RISE Stimulator limits at 250 milliamps, which has proved sufficient in clinical practice (Hofer et al., 2002; Kern et al., 2010).

It's worth noting that you won't necessarily use maximum current. I generally advise clients to increase the current intensity until they start to see a contraction, and then increase by about 10 per cent over that — what I would call the minimum effective intensity. Most people use considerably less than the device's maximum. But having the capability available ensures the device can produce effective contractions even in challenging cases where tissue resistance is high.

Appropriate Waveform Options

The standard waveform for denervated muscle stimulation these days is a biphasic rectangular current pulse. This is used because it delivers a defined, consistent charge per pulse, and the biphasic nature prevents net charge accumulation at the electrode-tissue interface, reducing the risk of electrochemical damage and skin irritation. Current-controlled delivery maintains consistent stimulation regardless of changes in tissue impedance — an important safety and efficacy feature.

However, there are situations where a triangular waveform becomes valuable. In fact, triangular waveform shapes were the “traditional” approach prior to the RISE research study. When denervated muscles sit adjacent to muscles that still have intact innervation — as commonly occurs in brachial plexus injuries or incomplete lesions — you need a way to selectively activate the denervated tissue without over-stimulating the innervated muscles alongside it. This is where the physiology of accommodation becomes relevant. Intact nerve fibres accommodate a slowly rising current: the nerve adjusts its threshold and does not fire. Denervated muscle fibres, however, have lost this accommodation ability and will respond to the slowly rising triangular pulse (Mayr et al., 2002). The result is selective activation of denervated tissue, which is clinically very useful.

A device for denervated muscle work should therefore offer both biphasic rectangular and biphasic triangular waveform options, along with current-controlled output.

Programmable Parameters

Denervated muscle stimulation is not a static treatment. Protocols evolve as training progresses, and the parameters need to be adjusted based on how the muscle responds over time. The Vienna rehabilitation strategy, developed through the RISE study, follows a staged approach: an initial twitch phase using very long pulses at low frequency to rebuild muscle excitability, progressing to tetanic stimulation at higher frequencies and shorter pulse widths as the muscle gains strength (Kern and Carraro, 2014). This progression requires a device that offers adjustable pulse width, adjustable frequency ranging from below 2 Hz to 20 to 30 Hz, adjustable current, adjustable timing for contraction duration and rest periods, and the ability to save and recall protocols so the user doesn't have to reprogram the device at every session.

Multiple Independent Channels

In practice, you'll typically need to stimulate multiple muscle groups, often bilaterally. If you're working with both thighs, for example, having at least two channels with independent control allows efficient treatment of different areas in a single session. This is a practical consideration rather than a physiological one, but it significantly affects the usability of a daily treatment routine that may last 30 minutes or more per muscle group.

What Doesn't Matter As Much As Marketing Suggests

The electrical stimulation market is full of features that are heavily promoted but largely irrelevant for denervated muscle work. Dozens of pre-set programmes, for example, are a common selling point for consumer devices — some advertise 50 or more programmes targeting different body areas and goals. For a denervated muscle, you need specific parameters that most pre-sets don't provide. A handful of appropriate programmes matter far more than a library of irrelevant ones.

Wireless connectivity and app control may be convenient, but they are not essential. The stimulation parameters are what determine outcomes, not how you access them. Similarly, sleek consumer design and aesthetic appeal don't affect efficacy. Medical-grade devices may sometimes look less sophisticated, but they deliver the performance that matters.

Perhaps the most misleading category is devices marketed for "EMS muscle building" or body sculpting. These are designed entirely for intact nerve-muscle systems and are irrelevant to denervated muscle applications. And if a device costs £50-£100, it almost certainly lacks the required output specifications. The electronics required to generate long-duration, high-current pulses safely are simply more expensive to design and manufacture.

The Reality of the Market

The vast majority of electrical stimulation devices available — whether in shops, pharmacies, or online — cannot help denervated muscles. This isn't a matter of opinion or brand preference. It's a matter of physics and physiology.

TENS units are designed to relieve pain via sensory nerves. They have no muscle-activation capability in denervated tissue. Consumer EMS and NMES devices are designed to stimulate motor nerves in intact systems — their pulse widths are too short and their currents too low by orders of magnitude.

Most clinical NMES devices share these same limitations, just with better build quality and regulatory compliance. Products marketed as ab stimulators, muscle toners, and similar fitness devices often have inadequate specifications despite their marketing claims. And FES cycling systems, despite being sophisticated rehabilitation tools that we use extensively for other applications, are designed for upper motor neuron injuries with intact peripheral nerves and will not activate denervated muscles.

The devices that actually work for denervated muscle are specialised products, generally available from medical device suppliers rather than consumer electronics retailers. This is an area where what you need and what is readily available do not overlap.

Devices That Work for Denervated Muscle

The RISE Stimulator

A small number of devices are specifically designed or capable of denervated muscle stimulation. I want to be straightforward here: this is a narrow field with limited options, and I'll describe what we know and use.

The RISE Stimulator was specifically developed for denervated muscle work and emerged directly from the European RISE study. Its design lineage can be traced from the original Stimulette Den2x described by Hofer and colleagues (2002) through to the current device. This matters because it means the RISE Stimulator is not simply a generic device with parameters that happen to overlap with what a denervated muscle requires — it was engineered from the ground up based on the protocols and specifications validated in the published clinical research.

It delivers pulse widths up to 200 milliseconds, current up to 250 milliamperes across two independently controllable channels, and includes pre-programmed protocols based on the Vienna rehabilitation strategy. A particularly useful feature is the impulse test function, which allows assessment of denervation status by generating a strength-duration curve — something we've long wanted as a simple, repeatable method of tracking progress over time. This is the device we most commonly recommend for spinal cord injuries that result in denervation of the lower limbs, and we supply and support this unit at Anatomical Concepts.

The Stimulette Edition 5 (also manufactured by Schuhfried Medizintechnik in Vienna) is a versatile clinical stimulator capable of both denervated muscle stimulation and other modalities, including standard NMES and pain management. We use this particularly for brachial plexus cases where pain management protocols may also be valuable alongside the denervation work.

The KT Motion device supports denovated muscle and also has some novel features such as EMG triggering.

We also work with KT-Motion and related products, which are often useful for upper-limb, brachial plexus and incomplete injuries. We will choose the appropriate product at an assessment. Everything we work with is designed both for home use or institutional use.

Why Specialised Devices Cost More

People sometimes express surprise at the cost of appropriate denervated muscle stimulators compared with consumer devices. I understand this reaction — many years ago, I was even accused of being a snake oil salesman when a critic looked at what appeared to be a small handful of electronic components and couldn't reconcile that with the price. The price difference, however, reflects genuine capability differences.

Generating long-duration, high-current pulses safely requires more sophisticated electronics than standard short-pulse stimulation. Higher output capabilities demand more robust safety features, including redundant systems that interrupt stimulation if electrode contact is compromised, current-controlled output to maintain consistency despite impedance changes, and balanced biphasic waveforms to prevent electrochemical tissue damage (Hofer et al., 2002). Devices with higher output also face more stringent regulatory requirements under EU Medical Device Regulation, increasing development and certification costs.

The market for denervated muscle stimulation is also simply much smaller than the market for general NMES. Smaller production volumes inevitably mean higher per-unit costs. And devices like the RISE Stimulator were developed through years of clinical research — the investment in the EU RISE study and subsequent work is reflected in the product. When you purchase a specialised device through a provider like ourselves, you're also investing in professional support, training, and ongoing clinical guidance — not just receiving a box of electronics with a user manual.

KEY POINT: Appropriate denervated muscle stimulators cost more than consumer devices because they do more, do it safely, and serve a specialised need. The cost reflects genuine engineering, regulatory, and clinical support requirements.

Why Electrodes Matter as Much as the Stimulator

The stimulator is only part of the system. Electrodes are equally important, and the wrong choice can undermine even the best device.

Standard self-adhesive gel electrodes — the kind used with most NMES devices — are typically 5 by 5 centimetres or 5 by 9 centimetres, giving a surface area of 25 to 45 square centimetres. They are designed for focused nerve stimulation at relatively low current densities. For denervated muscle work, they may not be appropriate for several interconnected reasons.

One fundamental issue is size. When stimulating an innervated muscle, you target the motor point — a specific location where the nerve enters the muscle. With a denervated muscle, there is no motor point to target because the nerve is no longer functional. Instead, every muscle fibre must be reached individually, which means the electrodes must ideally cover as much of the muscle surface as possible. Electrodes of 100 to 180 square centimetres are typical in denervated muscle protocols (Hofer et al., 2002). This is several times larger than standard gel pads.

The second issue is current density and safety. At currents of 200 milliamperes or more through a small 25 square centimetre electrode, the current density creates a real risk of electrochemical burns. The Den2x specifications documented maximum effective current densities of 2.7 milliamps per square centimetre on 70 square centimetre electrodes and 1.2 milliamps per square centimetre on 154 square centimetre electrodes (Hofer et al., 2002). Larger electrodes distribute current safely while engaging more muscle fibres.

The electrode types that work well for denervated muscle stimulation are wet sponge electrodes with carbon rubber backing, which are moistened before use and held in place with straps, and specialised safety electrodes used with conductive gel rather than adhesive. Both types can be cleaned and reused, which is important given that this treatment is used five or six days per week — the ongoing cost of disposable gel electrodes at that frequency would be prohibitive. Whichever type you use, good contact with the skin is essential, and the electrodes should be large enough to cover as much of the target muscle as possible.

Having the above as the rule, I'll now tell you about the exception. In some cases, we will use small chilled electrodes. This might be when we need to target a specific small muscle. In these cases, we consciously limit the maximum current for safety to less than 100 mA.

Assessment Before Purchase

Before purchasing any device, I would strongly encourage you to seek a professional assessment first. This is not a sales tactic — it's a genuine clinical recommendation based on the reality that denervated muscle stimulation is a significant time- and money-commitment, and getting it right from the start matters.

Assessment serves several important purposes. It confirms whether your muscles are indeed denervated, which is not always as straightforward as it might seem. Not all weakness or paralysis indicates denervation — upper motor neuron lesions present differently and require different treatment approaches. Assessment identifies which specific muscles are affected, establishes baseline measurements for tracking progress, and determines appropriate starting parameters for your individual situation. It also identifies any contraindications that might apply and, importantly, helps set realistic expectations. Outcomes depend heavily on the time since injury, the extent of structural changes in the muscle, and individual factors. Research from the RISE study shows that patients starting home-based stimulation within one year of injury achieve significantly better outcomes than those starting after three to five years (Kern and Carraro, 2014), though we have seen benefits even in people with long-standing injuries.

The device investment is substantial. Ensuring it's the right choice for your situation, and that you start with appropriate protocols, simply makes sense.

What We Offer at Anatomical Concepts

At Anatomical Concepts, our approach begins with understanding your individual situation. This typically involves an initial assessment — testing muscle response, identifying treatment targets, and confirming the suitability of electrical stimulation for your case. Based on that assessment, we make equipment recommendations tailored to your specific needs, not a one-size-fits-all approach.

When equipment is provided, we ensure thorough setup and training so that you know how to use it safely and effectively. We develop a personalised stimulation protocol with appropriate parameters for your starting point, following the staged approach established by the Vienna rehabilitation strategy: beginning with twitch contractions to rebuild excitability, then progressing to tetanic contractions as the muscle responds. Ongoing support includes periodic reviews, troubleshooting, and protocol adjustment as your treatment progresses over months and years.

We supply the RISE Stimulator, Edition 5 device or the KT-Motion along with appropriate electrodes and accessories. But more importantly, we provide the expertise to use them effectively. The equipment is the tool; knowing how to apply it to your specific situation is what makes the difference.

Making Your Decision

When choosing a stimulator for a denervated muscle, the essential steps are simpler than you might expect — once you understand what actually matters, most options are quickly eliminated.

Start by verifying the technical specifications. The device must offer a pulse width of at least 100 milliseconds, a current output of at least 200 milliamps, and appropriate waveform options, including biphasic rectangular or triangular pulses. If a device cannot meet these minimum requirements, no other feature compensates for that limitation.

Consider the source and the support available. Is this a Certified medical device designed for or validated with denervated muscle in mind? Does the supplier have relevant clinical experience, and can they provide ongoing guidance? A device without professional support is like a prescription without a clinician — technically possible, but unlikely to produce the best outcome.

Seek professional guidance before and after purchase. Assessment before purchase ensures you're making the right choice. Post-purchase training ensures you use the equipment safely and effectively. Ongoing clinical support ensures your protocols evolve appropriately as your treatment progresses.

Be wary of shortcuts. Consumer devices are not "almost as good" — they operate on entirely different physiological principles. No app, workout programme, or marketing claim compensates for inadequate output specifications. And think long-term: this is equipment you'll use daily for months or years. Quality, reliability, and professional support have genuine ongoing value.

Conclusion

Choosing a stimulator for a denervated muscle, while it may seem daunting, becomes straightforward once you understand the underlying physiology. The requirements are not arbitrary preferences — they are dictated by the biophysics of directly activating muscle fibres that have lost their nerve supply. The essential specifications — sufficient pulse duration, adequate current output, appropriate waveforms — are well established by decades of research from Kern, Carraro, Mayr, and their colleagues, and confirmed by recent reviews (Chu et al., 2025). The devices that meet these requirements are specialised products, not consumer electronics.

If you're considering denervated muscle stimulation and want guidance on equipment selection, please [contact us](/contact). We can help you understand your options and make an informed decision based on your individual situation.

References

Chu L, Jarvis JC, Andrews BJ, FitzGerald JJ. Electrical Stimulation of Denervated Muscle: A Narrative Review. Artificial Organs. 2025. DOI: 10.1111/aor.70076.

Eberstein A, Eberstein S. Electrical stimulation of denervated muscle: is it worthwhile? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1996;28(12):1463–1469. DOI: 10.1097/00005768-199612000-00004.

Hofer C, Mayr W, Stöhr H, Unger E, Nishida T. A stimulator for functional activation of denervated muscles. Artificial Organs. 2002;26(3):276–279.

Kern H, Carraro U. Home-Based Functional Electrical Stimulation for Long-Term Denervated Human Muscle: History, Basics, Results and Perspectives of the Vienna Rehabilitation Strategy. European Journal of Translational Myology. 2014;24(1):3296. DOI: 10.4081/ejtm.2014.3296.

Kern H, Carraro U. Home-Based Functional Electrical Stimulation of Human Permanent Denervated Muscles: A Narrative Review on Diagnostics, Managements, Results and Byproducts Revisited 2020. Diagnostics. 2020;10(8):529. DOI: 10.3390/diagnostics10080529.

Kern H, Carraro U, Adami N, Biral D, Hofer C, Forstner C, Mödlin M, Vogelauer M, Pond A, Boncompagni S, Paolini C, Mayr W, Protasi F, Zampieri S. Home-based functional electrical stimulation rescues permanently denervated muscles in paraplegic patients with complete lower motor neuron lesion. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2010;24(8):709–721. DOI: 10.1177/1545968310366129.

Kern H, Hofer C, Modlin M, Mayr W, Vindigni V, Zampieri S, Carraro U. Denervated muscles in humans: limitations and problems of currently used functional electrical stimulation training protocols. Artificial Organs. 2002;26(3):216–218.

Mayr W, Hofer C, Bijak M, Rafolt D, Unger E, Reichel M, Sauermann S, Lanmuller H, Kern H. Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) of denervated muscles: existing and prospective technological solutions. Basic and Applied Myology. 2002;12(6):287–290.

Mödlin M, Forstner C, Hofer C, Mayr W, Richter W, Carraro U, Protasi F, Kern H. Electrical stimulation of denervated muscles: first results of a clinical study. Artificial Organs. 2005;29(3):203–206. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2005.29035.x.

Further Reading

Why your NMES product probably doesn't work with denervated muscle

Understanding the cost of care: why medical-grade stimulation devices outprice consumer units

Creating an assessment report and training plan for the RISE Stimulator

Denervated muscle stimulation: why optimal intensity beats maximum intensity

Can electrical stimulation help denervated muscles recover?