Pressure Reduction vs Complete Offloading: Why the Distinction Matters for Tissue Viability

The terms get used interchangeably in clinical practice. Pressure reduction. Offloading. Heel protection. Redistribution. But they are not the same thing. And the distinction matters to clinical outcomes —particularly at the heel, where anatomy conspires against us.

The 2025 International Pressure Injury Guideline makes this explicit. For heels, the recommendation is unambiguous: heels should be "fully free from contact with the support surface." Not reduced pressure. Not redistributed pressure. Zero contact.

This article explains the biomechanical difference between pressure reduction and complete offloading, why it matters specifically at the heel, and what the evidence shows. Let's be clear about definitions first.

Pressure reduction spreads the load; complete offloading eliminates it from the area at risk

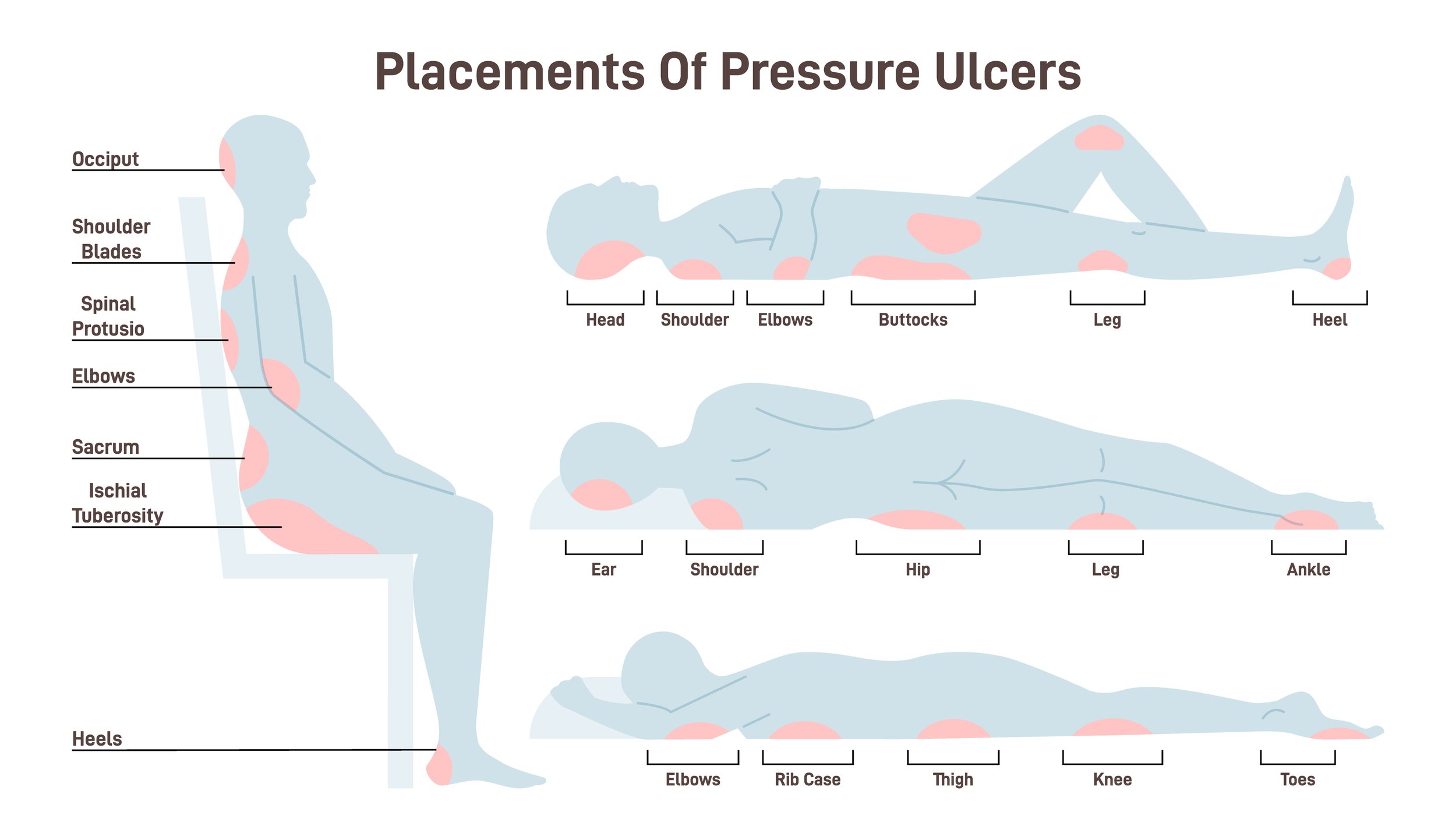

Pressure reduction—sometimes called pressure redistribution—works by spreading the force applied to tissue over a larger contact area. Thereby reducing the pressure per unit of area. Consider someone lying on a firm surface bed. Bony prominences (areas with very little tissue covering) are typically where high pressures are found. A foam overlay, for instance, that conforms to the body's contours can be expected to distribute the applied pressures more evenly than a standard mattress. This approach has merit for many body surfaces. The sacrum and buttocks, with their larger contact areas and more substantial soft tissue coverage, can benefit from redistribution strategies. In fact, these are the only strategies that work for areas like this.

Pressure ulcers tend to occur where there are bony prominences. The heel area requires total pressure relief, not just reduction.

Complete offloading works differently. Rather than spreading and reducing the load, it removes contact entirely. The heel floats free of any surface, suspended so that no pressure acts upon it at all. Perhaps even more important is the fact that there is no contact between a support surface and the area at risk. This means that there is no shear force being applied, which we know to be especially detrimental to tissue viability.

The clinical question is: which approach does the heel actually need?

The heel's anatomy makes redistribution approaches inadequate.

The heel presents a unique biomechanical challenge. Consider what we're working with:

A small, curved bony prominence (the calcaneus)

Minimal soft tissue padding

A thin dermal layer directly over bone

End-artery blood supply easily compromised

A contact surface measured in a few square centimetres, not the larger areas available at the sacrum

When pressure acts on such a small area, redistribution has limited scope. There simply isn't enough surrounding tissue to spread the load to. A pressure-redistributing surface may reduce peak pressures and shear forces, but it cannot eliminate them—and the heel's anatomy tolerates very little mechanical insult.

The 2025 pressure ulcer guidelines acknowledges this directly: "reducing pressure and shear... are the most important focus in prevention, given the small heel surface area where redistribution of load and forces can be challenging."

In other words: the heel is too small for redistribution to work reliably.

Shear forces compound the problem.

Pressure isn't the only destructive force at work. As we mentioned above, Shear—the lateral movement of tissue layers against each other—is arguably more damaging to blood supply than perpendicular applied pressure.

When the heel rests on a surface, even a soft and compliant one, the skin adheres while deeper tissues shift. This stretches and occludes the blood vessels running between tissue planes. Research has shown that shear is extremely efficient at shutting off capillary blood flow—more so than direct compression.

Pressure-reducing surfaces address perpendicular force but do little about shear. A gel pad or foam overlay may cushion the heel, but as the patient moves—or as the surface shifts beneath them—shear forces still act on the tissue.

Complete offloading eliminates both. When the heel floats free of contact, there is no surface to generate either pressure or shear. The destructive mechanical forces simply don't exist.

The evidence strongly favours offloading over reduction.

This isn't theoretical. Comparative studies have examined the difference directly.

One randomised controlled trial found that patients using heel offloading boots had a 0.4% incidence of heel pressure injuries compared to 8.4% with standard care. That's a twenty-fold difference.

Another study comparing pressure-reducing devices (specifically the Foot Waffle) with standard pillow elevation found that pressure ulcers developed significantly sooner in the device group—10 days versus 13 days. The pressure-reducing device was four times more likely to fail at suspending the heel off the bed.

Units implementing systematic heel offloading with suspension devices report 75% reductions in new heel pressure ulcer formation.

The pattern is consistent: complete offloading outperforms pressure reduction at the heel.

Common methods fall short of true offloading.

In practice, many interventions labelled as "heel protection" are actually pressure reduction—and not particularly effective pressure reduction at that.

Pillows remain widely used. In theory, elevating the lower leg on a pillow suspends the heel. In practice, pillows compress, shift, and allow the heel to sink until it contacts the surface. They require constant repositioning and vigilance.

Fluid-filled gloves were once common. The 2025 guideline explicitly recommends against them: they fail to maintain position, redistribute pressure inadequately, and increase skin moisture. They should no longer be used.

Egg-crate foam overlays provide minimal pressure reduction. The guideline states they are "insufficient for prevention" and may aid comfort but not pressure redistribution.

Sheepskin alone is similarly inadequate as a sole intervention, despite decades of use.

Each of these methods attempts pressure reduction rather than complete offloading—and at the heel, that distinction matters.

Effective heel offloading requires proper device design.

True heel floating syspension requires a device engineered for the purpose. The heel must be suspended clear of all surfaces—mattress, footplate, and the device itself—while the leg is supported through calf and foot contact.This is the principle behind the PRAFO range of ankle foot orthoses. We have worked with PRAFO devices for over thirty years precisely because they achieve complete heel suspension rather than pressure reduction.

The design distributes load through the calf and dorsum of the foot—areas with more tissue coverage and larger surface areas—while the heel floats entirely free. No contact means no pressure and no shear.

The metal upright structure maintains this position reliably, resisting the forces (including high plantarflexion tone in stroke patients) that would otherwise push the heel back into contact with a surface.

This is not the only device capable of achieving complete offloading, but it is the one we have seen work consistently across three decades of clinical practice. It is also the only one which has the metal upright structure which is necessary for structural integrity.

The guideline language is deliberate.

The 2025 International Pressure Injury Guideline uses specific language: heels should be "fully free from contact with the support surface."

Not mostly free. Not reduced contact. Fully free.

This is described as "floating heels"—a term that captures the mechanical requirement precisely. The heel should hover, suspended, touching nothing.

When assessing any heel protection intervention, this is the standard to apply. Does it achieve full suspension? Or does it merely reduce pressure while maintaining contact?

The distinction matters because the heel's anatomy leaves no margin for half-measures.

Clinical implications are straightforward.

For clinicians managing patients at risk of heel pressure ulcers—whether in intensive care, post-operative recovery, stroke rehabilitation, or spinal cord injury—the evidence supports a clear approach:

682SKG PRAFO model with adjustable dorsiflexion/ plantarflexion and a metal upright structure with Kodel liner

1. Identify patients at risk early in their care pathway

2. Implement complete offloading rather than relying on pressure redistribution alone

3. Select devices designed for heel suspension not general pressure reduction

4. Verify that heels are actually floating—check that no contact exists between heel tissue and any surface

5. Maintain offloading across care settings—protection that works only in bed fails during mobilisation. This is where the Prafo range really scores due to the metal upright and in-built walking base. The same device can be used for bed, rest, protection, and for mobilisation. When there is a risk of plantar flexion contracture development, the metal structure of the praful range provides necessary resistance to such developments.

The 2025 guideline gives us evidence-based language to advocate for appropriate interventions. When budget holders question the cost of proper offloading devices, the comparative injury rates provide a clear answer.

Prevention is not merely better than treatment. At the heel, prevention through complete offloading is the only approach the evidence supports.